#WLS2019 Global Report

We Thank Our 2019 Hosts for Making the Inaugural Summit a Grand Success

Mario Di Giulio, Partner, Pavia e Ansaldo, Italy

Chrys Ahmadu, Attorney-General of Plateau State, Nigeria

Jeffrey Aresty, President/CEO, Aresty International Law, United States

Lyria Bennett Moses, Director, Allens Hub for Technology, Law and Innovation, Australia

Linda Bonyo, Director, Africa Law Tech Association/CEO Lawyers Hub Kenya, Kenya

Larry Bridgesmith, Chair, Alternative Dispute Resolution Commission of the Tennessee Supreme Court/Adjunct Professor, Program on Law & Innovation, Vanderbilt Law School, United States

Eva Bruch, Faculty Advisor, Digital Legal Exchange/Partner, Alterwork, Spain

Victoria Cino, Content Development Associate, Lexis Nexis, Canada

Dr. David Cowan, Author & Associate Lecturer, Law Department, Universty of Maynooth, Ireland

Javier de Cendra, Dean Faculty of Law and Business, Universidad Fancisco de Vitoria, Spain

Rhodrigo Deda, Editor Executivo de Vida Pública, Gazeta do Povo, Brazil

Alberto Elisavetsky, Director del Observatorio del Conflicto, Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Argentina

Mariana Faria, Lawyer/Journalist, Brazil

Paula Figueiredo, Fundadora e Presidente, Comissão de Direito para Startups – OAB/MG, Brazil

Gibran Freitas, COO, Legal Doctrine/Co-Founder Legal Tech Africa, France

Nicolino Gentile, Salary Partner, BLB Studio Legale – Benedetti Lorusso Benedetti, Italy

Brendan Guildea, BL Barrister-At-Law (practicing) and Tech enthusiast, Ireland

Iryna Hliabovich, Angel/Legal Advisor & Lecturer Belarusian State University, Belarus

Catherine Kubrak, CEO, Education Center/PM, Clover Consult Legal Agency, Belarus

Josh Lee Kok Thong, Chairperson, ALITA/Legal Policy Manager for AI Governance, IMDA, Singapore

Alejandro Luna, Partner/CTO, Lawit Group, Mexico

Juan Luna, Founder, Lawit Group, Mexico

Themba Mahleka, Innovating Justice Agent, HiiL/Legal Consultant, IMANI, South Africa

Robin Moe, LegalTech Developer, EY, Sweden

Marisa Monteiro Borsboom, CEO/General Consel, MQM Legal Center/CLO and Board Member Women in Tech, The Netherlands

Terri Mottershead, Executive Director, Center for Legal Innovation, Australia

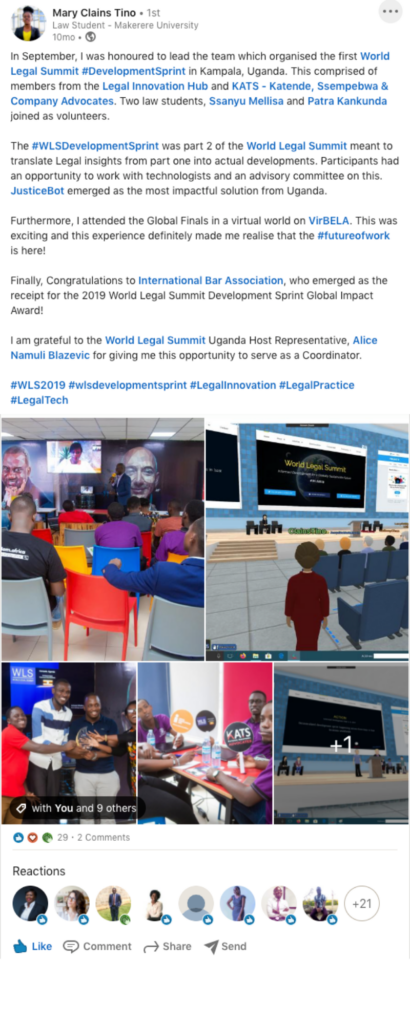

Alice Namuli Blazevic, Partner/Head of Technology & Innovation, Katende, Ssempebwa & Co. Advocates, Uganda

Paul Neo, COO, Singapore Academy of Law, Singapore

Rahila Olu-Silas, Chief State Counsel, Plateau State Ministry of Justice Nigeria

Kamel Oumnia, Co-Founder & Sr. Legal Advisor, IncubMe/Digitsole, Algeria

Adam Oxford, Head of Digital, Mail & Guardian/ Justice Accelerator Co-Head, HiiL, South Africa

Quddus Pourshafie, Founder, FutureLab.Legal, Australia

Patricia Razquin, Head of Marketing, Allen & Overy, Spain

Aileen Schultz, Founder/President, World Legal Summit & Sr. Mng., Thomson Reuters Labs, Canada

Linda Seely, Director of Dispute Resolution Section, American Bar Association, United States

Nicola Shaver, Managing Director, Infotropic Media, United States

Paula Silva Lopes, Director, Portuguese Chamber of Commerce, Portugal

Kareena Starkova, Communication Manager, Touch Education Platform, Belarus

Holger Zscheyge, Managing Director, Infotropic Media, Russia

Want to get your organization involved?

We also thank our ambassadors, expert panelists, local sponsors and participants for promoting sustainable technology in their countries.

Learn about which countries are prepared to adopt decentralized identity frameworks.

Survey of the regulatory landscape for our WLS Techno-Legal Pillars, beta available.

Preface

“Fire was an invention that propelled civilization, but there is no doubt that fire has also been misused. The same can be said about new technologies.” – Panelist Madrid, Spain WLS 2019

The World Legal Summit (WLS) launched in 2019 as an experiment in technology governance to bridge the siloed discussions currently happening. Our vision is to bring technical and legal communities together around a shared understanding. Around the world today, we see engineers and scientists inventing and improving new technologies that are reimagining our future, a future that could and should be beautiful for us all. However, to achieve such a future, various communities need to come together and develop a shared understanding and collaborate on the sustainable evolution of these technologies, and the uniquely powerful global systems they are making possible.

While legal and governance expertise are emerging around the world to solve some of the issues that underlie the governance of these technologies today, these expert communities are often focused on one or just a few jurisdictions. More often than not, the voice of the technologist is missing from these conversations. The WLS seeks to support a global conversation between these disparate communities, thereby building a community-driven platform inclusive of all stakeholders for discussing and applying legal frameworks governing new technologies.

It is our sincere belief that shared insights from around the world can be distilled to produce a common understanding far superior to the predominantly centralized frameworks currently in place. The WLS intends to promote this collective vision and over time uncover a common dialogue that represents a community of truly global-minded citizens. We invite you to read and learn more about our work, and hope that you will join us in co-developing a globally sustainable future.

Yours in legal transformation, The WLS Team

Review Panel

WLS Research, Editorial and Authorship

Executive Summary

This report is a collection of insights from the inaugural gathering of the 2019 World Legal Summit. Organizations from across the academic, non-profit, legal, government, and technology sectors participated in the WLS in over 30 cities across more than 20 countries. Each host location contributed to discussing and forming insights examining key categories of technology legislation and policy within their regions based in the following three WLS Technology Pillars:

This compilation of insights from the host locations also includes expert contributions and additional insights from existing legal databases and research publications. The report was collated and written by WLS writers and researchers.

Content Organization

Organized by each technology pillar, the report includes a regional breakdown covering the technology and legal landscape for categories across each region covered, which are Africa, the Asia Pacific, Europe, Latin America, and North America.

The technology landscape provides an overview of the research, development, and adoption of technologies within that region, reviewing such factors as public and private investment, level of talent and skill concentration, and adoption impediments and supports. The factors addressed for each region are not necessarily the same, but rather a summary of available research and insights contributing to the discussion. In some regions, many technologies are more mature contributing to a wider scope of available information, while in other regions these technologies are still nascent.

The legal landscape reviews the legislative frameworks being developed or enacted within a particular region, with a focus on the emergent regulatory landscape; the cutting edge new laws and proposals dealing with these technologies, and those regional frameworks that are setting a precedent for global standards.

Perspective

While the WLS aims to remain politically neutral, a few core values inform the report’s perspective and tone. These values centre on concepts driving future independent global systems, including those dealing with global governance and the idea of a global citizenry or digital democracy. The report reflects insights and research encompassing these values, and highlights regional frameworks more aligned with these values.

Considerations

The report is the product of an inaugural initiative that intends to develop and grow over time. This report builds on the work of 33 locations that hosted the first year across 25 countries, with the number of participants ranging widely from one location to the next; with hundreds of participants at some locations and small group discussions at others. Not all regions of the world were covered, nor were the locations involved unanimous in structure. This report distills the contributions of all participants and aims to honor their incredible efforts.

Though for some regions little to no discussion of legal frameworks for a particular topic may be present, that does not necessarily mean that laws governing that domain are non-existent within that region. For example, some laws may be industry specific, regulated at the local level, or may contain terminology that is outdated and thus not surfacing in discussions of current terminology, like “autonomous systems” or “digital identity”.

Additionally, we must acknowledge some likely margin of error in distilling all submitted insights into a single coherent vision. Given the very nature of the innovative domains the WLS explored, the value of harvested information decays over time and is continually in flux. Further, the range of submissions differ by length and quality. An expert review panel was established for this report to reduce this margin of error to the greatest extent possible for this inaugural version.

Throughout this report images, quotations, key takeaways, and other content frame the contours of a global conversation. These added features were deliberately collated from the WLS2019 initiative and many were submitted explicitly for this report. Any content independently authored does not necessarily reflect the WLS’ single perspective, but is instead intended to open dialogue between stakeholders of varying perspectives.

As the WLS evolves and the community of experts grows, we aim to continually adapt our understanding of technology governance and invite all stakeholders to share their perspectives. We hope to create a living, breathing dialogue around critical issues shaping our shared global future.

Identity & Decentralized Ledger Technologies

Africa // Asia Pacific // Europe // Latin America // North America

Introduction

Identity is core to the functioning of future global systems. This section explores the regulatory and technology landscape for digital identity frameworks and the decentralized technologies supporting their evolution. The scope of this material is limited to reviewing the regulations and technologies that explicitly work at the intersection of new identity frameworks. Extraneous topics examining cryptocurrencies and other use cases for decentralized technologies are addressed only insofar as they may contribute to the discussion of identity.

For example, while cryptocurrencies and related regulations are not directly aligned with the evolution of digital identity frameworks, advancements in these domains are inherently interdependent with issues of identity. For example, the crypto economy is enabled by digital identities with regard to network access. If a government enables crypto economies through technology adoption, investment, and regulation, decentralized digital identity is inherently embedded in this discussion. While governments considering decentralized ledger technologies (DLTs) may not yet be giving the same attention to decentralized identities in terms of investment and development of the needed regulatory frameworks, they are nonetheless building on a foundational infrastructure and its regulation in other domains and that foundation could enable accelerated adoption of emergent regulatory frameworks for digital identity as well.

Africa

Use of decentralized technologies certainly is not new in many African countries, although much of the adoption to date has been within and through digital economies. While eGovernment and digital identity systems are quite mature relative to global trends, more attention needs to be paid to the possible benefits of decentralized technologies like blockchain and the adoption of these technologies in identity systems. Many African nations are considered to be forerunners in adopting digital identity systems, with many countries managing most of their citizens’ needs digitally. Much of this digital infrastructure is beyond the prototype stage and well on its way to mass adoption across the continent, and in a couple cases is also exploring the use of DLT. For example, Sierra Leone is reportedly the first ‘Smart Country’ in the world, focussed on ensuring a digital credential framework for its citizens. Further, one African nation, Tunisia, is currently the world’s forerunner for a central bank government-issued digital coin based on DLT. At present, Tunisia is the first and only known country to successfully issue a fiat digital currency in this way, having done so in 2019.

“… all these Government agencies individually hold functional data of a person but are not integrated in a way that promotes efficient service delivery. The Huduma Bill once issued is a single source of identification and is both functional and foundational.” Panelist Kenya, WLS 2019

In addition, significant progress with technology adoption has been seen in the private sector across Africa. For example, blockchain-based skill-identifiers have been issued to students and administrators in Kampala through a pilot program executed by a Norwegian-based company focused on solving global issues of identity theft and credential fraud. Another great example is the uptick of these technologies to support building economic participation for traditionally bankless or invisible populations, enabling those without any form of government-issued identification to participate in the economy through digital and decentralized means. This growth is largely due to the need for improved infrastructure and security in these domains.

Organizations like ID4Africa have gained momentum in recent years, earning the support of government officials across much of the continent. As of the writing of this report, 48 of the 55 African nations are members of the ID4Africa movement, an initiative directed at developing digital infrastructure and harmonizing systems across the continent. Though there is this attention to digital identity, effectively no attention is being paid to developing a decentralized framework. The organization seeks to support identity for all in Africa. Of the nations that maintain eGovernance, citizens’ identities are solely dependent on centralized issuance and management by institutions that act as intermediaries between the person and the person’s associated legal identity.

Jos Nigeria, WLS 2019

Algeria, WLS 2019

Kenya, WLS 2019

As explained more fully below, African laws lag on building the necessary data protection and legal frameworks for protecting the rights and interests of nations’ citizens. For most nations, substantial distrust in government and its capacities to provide due diligence in protecting individuals rights and interests prevails. This directly affects eGovernance systems’ ability to gain mass approval, even though digital identity use is mandatory in many nations , causing tension between the further development of digital systems and citizens’ interests.

Kenya, WLS 2019

During WLS2019, much debate and discussion concerned the Huduma Bill proposed in Kenya. Input from those outside of Kenya surfaced much of the sentiment across African countries regarding current digital identity systems. The Huduma Bill intends to establish a National Integrated Identification Management System (NIIS) that assigns individuals a unique identification number. Although the system assigns this number in association with collected biometric and functional data about the individual, such as their DNA, retinal scans, voice waves, and the GPS coordinates of their residential address, the Bill does offer some notable benefits. A member of the Bill’s drafting committee, who was a panelist at the WLS2019 summit, enumerated the major benefits as follows.

Single source of identification: Kenya currently runs multiple identification and registration systems that are not integrated. One must separately register for Birth Notification, Birth Certificate, ID Card, Voters Card, Passport, Marriage Certificate, Tax PIN, National Health Insurance Fund, and National Social Security Fund. All these government agencies hold functional data about a person separately, leading to inefficient service delivery and increased data security risks.

Financial inclusion and efficient service delivery: Digital identity is hoped to promote inclusion and access to credit facilities.

Uganda, WLS 2019

The main issue with the Bill presented in this discussion concerned lack of data protection laws surrounding the proposed Bill. Without necessary protections, exploiting this data about citizens could occur through corrupt government agendas and its acquisition and use by foreign threats seems inevitable.

Perumall Ashlin, Baker McKenzie, stressed the importance of Article 6 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights “Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law” as well as the Sustainable Development Goal 16.9 “By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration.” South Africa, WLS 2019

The need for better data protection was expressed at the WLS2019 Jos summit in Nigeria regarding implementation of the National Identity Management System (NIMS). Experts suggested that a system like the NIMS “is imperative to correct the oversights of previous ID systems and to usher in a new system that meets international standards and best practices.”

One of the greatest promises of digital identity infrastructure is currently stateless or invisible peoples’ identification and participation in the economy. These people currently have no government issued identification and their assets often are not legally registered; for example, intergenerational land and property inheritance . Without legal registration, these populations remain vulnerable to land theft and other issues. Decentralized identity frameworks and related digital infrastructures could support the appropriation of property rights to many of the world’s poorest populations.

The benefits of decentralized technology may not be a priority everywhere. For example Kenyan WLS2019 panelists expressed this concern about the existing law’s “…potential for exclusion of several minority groups including stateless communities as the law requires presentation of identification documents in order to acquire the Digital ID.” If some form of identification is required to participate in the digital transformation, currently stateless or invisible populations will remain disadvantaged.

Asia Pacific

Like many other regions and multinational organizations around the world, APAC countries are more focused on the economic impact of decentralized technologies and cryptocurrencies, and less focused on the purely infrastructural application of these technologies. For example , crypto mining farms are common across APAC. In fact, the region holds an estimated ⅖ of the top 50 crypto exchanges worldwide. Indeed, over 35% of all Bitcoin is transferred to the APAC region. This data suggests that compared with the rest of the world, APAC countries are by and large spearheading the use of cryptocurrencies.

“The notion of ‘self-sovereign identity’ has gained traction as people try to reclaim disparate parts of the data they share” Panelist, Sydney Australia, WLS 2019

Singapore, WLS 2019

While it may be true that APAC leads adoption of crypto economic infrastructure, broader applications of the technology, including digital identities, has been slower. Yet, promising signs suggest that attention could shift soon. For example, Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, Temasek, has invested in the growth of blockchain-based projects dealing with digital identity infrastructure. Additionally, in South Korea several private organizations, including telecommunication companies , technology companies, and banks, have partnered to develop decentralized identity systems, with a decided nod toward self-sovereign systems. China has stated that its considerations of a central bank digital coin explicitly exclude consideration of distributed ledger technologies due to their current inabilities to scale, suggesting similar constraints with identity infrastructure. Notably there is strong indication to suggest that blockchain and DLTs are being considered as a critical priority in China for areas such as copyright protection, and APAC overall is prioritizing blockchain skills, with the region’s blockchain industry estimated to be worth $16 billion by 2024.

“The issue and phenomena of individuals identity…changing based on how they are treated by a governing body is evident without technology but exacerbated by the application of technology. Australia’s ‘Robo-debt’ scandal was a remarkable example of what is going on.” Panelist, Adelaide Australia, WLS 2019

Digital identity infrastructure (a precursor to decentralization) across APAC is forecast to effectively leapfrog other parts of the world that are weighed down by cumbersome analog systems. Along with Africa, the APAC region is estimated to account for the largest portion of the 150% estimated growth of government issued digital identity technology by 2024. Singapore is working on developing a National Digital Identity (NDI) platform, a cryptographic system for transacting online. In Australia, a Digital Identity Framework that models decentralization is already accessible to its citizens on a voluntary basis. The Australian system ensures users control their own data and accessing government services remains private . Taken as a whole, however, the ease of use of non-DLT based technologies for the adoption of digital identities suggests that a truly decentralized identity infrastructure may not be a priority for the APAC region.

As in many other regions worldwide, APAC is struggling to maintain relevant regulations supporting adoption of new identity frameworks. For example, Australian WLS2019 panelists expressed concerns regarding the many challenges associated with regulating this environment, including updating definitions for what constitutes personal data and identifiable information, as well as creating standards maintained across both national and international borders.

“The issue and phenomena of individuals identity…changing based on how they are treated by a governing body is evident without technology but exacerbated by the application of technology. Australia’s ‘Robo-debt’ scandal was a remarkable example of what is going on.” Panelist, Adelaide Australia, WLS 2019

Sydney Australia, WLS 2019

However, the maturity of the legal and regulatory environment surrounding cryptocurrencies, and by extension blockchain or DLT, is more mature in APAC than most other parts of the world. For example, the Australian Trusted Digital Identity Framework (TDIF) outlines as key principles governing its use privacy, security, and integrity. While frameworks like these do not constitute a mature regulatory environment, they do reflect progress. Similarly, Singapore is considered a crypto haven, and promotes the development and regulation of these technologies for a wide range of use cases; the Monetary Authority’s regulatory sandbox is a great example of this focus.

“…our digital identity has taken over our traditional identity…the concept of identity in the digital world is still a work in progress.” Panelist, Brisbane Australia, WLS 2019

Yet much of the legislative environment outside of Singapore specifically for cryptocurrencies is focused on banning or limiting their use, in effect to buy time until the technology and its application are better understood and technically scalable. Although relative regulatory clarity in Singapore has made it a magnet for many crypto companies operating in APAC, regional regulatory limitations are inhibiting the acceleration of use cases beyond cryptocurrencies, including the adoption of distributed identity frameworks.

Europe

Several European countries are notoriously leading the way when it comes to decentralized systems and digital identities. Switzerland was one of the first countries to accept bitcoin as a form of payment, Malta attracted large scale investment after its announced aspirations of becoming a ‘blockchain island’, Estonia is the forefather of eGovernance systems with its e-citizen passports and digital identity infrastructure based on blockchain technologies, and Western Europe is one of the top regions for investment in the development of blockchain technologies.

The European Union is highly supportive of the research, investment and development of blockchain and DLT and their many applications. In several ways, the EU’s considerations of blockchain and DLTs are more mature than other parts of the world. Much of the world is still caught up with the crypto hype, possible real world adoption, and necessary regulatory frameworks to enable or disable these new economic structures. The EU’s considerations of these technologies have matured beyond its applications as financial instruments, to prioritizing the enablement of globally inclusive governance and initiatives like international standards-building and cooperation and more infrastructural applications of the technologies. Furthermore, the GDPR has provided a strong basis for regulating and protecting persons’ data as this information shifts into use in new identity systems.

The Hague, WLS 2019

When it comes to digital identities, the EU too is a forerunner in encouraging adoption of digital identities, with its launch of the 2015 eIDAS that encouraged the ‘Digital Single Market’ or ‘Single European Market’ that facilitates cooperation of eID systems across European nations. Furthermore, the European Commission is facilitating discussion about new era identity systems like decentralized IDs and Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) frameworks that the eIDAS framework supports. These discussions have resulted in the European Self Sovereign Identity Framework (ESSIF), supported by the European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI), and progress toward a bridge with the eIDAS framework.

“Legal text translated to algorithms and code would significantly help the developers to understand the borders of the legislator’s intentions…further, the use of human language may provide obstacles on its own, boosting the argument for using a universal language, such as math or programming languages.” Panelist, Sweden, WLS 2019

As an example of what these new frameworks might look like at a national level, Malta took a revolutionary step in being the first country globally to issue Blockcerts for academic credentials, “…an internationally portable, instantly verifiable digital format”. Another great example is Alastria, a Spain-based blockchain association supported by hundreds of public and private companies, having built their own public-permissioned blockchain with progress toward EU adoption. Sweden, in fact, has had a Swedish Personal Identification Number system for digital identification for many years now; however, much of the population is still without a registered ID, meaning the associated services are not yet available to all citizens. Although some non-EU nations, such as Russia and Croatia, have yet to adopt a robust eID infrastructure, they do plan to do so.

The adoption of these technologies in Europe is definitely owed in large part to the rate at which lawmakers have been able to keep pace with the changing demands on the regulatory landscape. The EU and non-EU member nations, have prioritized development of the regulatory frameworks needed to foster innovation in these technological domains. As the technologies become better understood and their use cases broadened, the legislative environments across Europe have proven to be highly adaptive. Switzerland, for example, is already a forerunner in setting regulatory standards for the use of blockchain technologies and regularly amends its federal laws to accommodate the changing landscape, though predominantly dealing with cryptocurrencies. Examples of state or municipal level progress, such as the “Barcelona Charter of Citizens’ Rights in the Digital Era” also exist.

“Defendants of the existence of an identity for each person, differ on who should be the main body which has the capacity to certify that an individual is who he or she claims to be.” Madrid Spain, WLS 2019

The EU prioritizes building ‘improved legal certainty’ in dealing with blockchain and the applications of DLTs, highlighting smart contracts and tokenization as two key areas in need of lawmakers’ attention. Further, the EU has launched a study on Blockchains: Legal, Governance and Interoperability Aspects, dedicated to “…setting the right conditions for the advent of an open, secure, trustworthy, transparent, and EU law compliant data and transactional environment”. This study digs into the broader applications of DLTs, such as the interoperability of governments and applications of decentralized consensus. This progress folds over into the digital identity space, with most of Europe using an eID system and EU members already cooperating on the further development of the eIDAS regulatory framework.

Combined, the growth of the regulatory landscape enabling DLTs and promoting cooperation amongst eID systems indicates that much of Europe could be moving toward true decentralization. In particular, its promotion of the single ID network and discussion of new identity management systems like SSIs strongly indicate that a decentralized identity framework could be in much of Europe’s near future.

Rome Italy, WLS 2019

Barcelona Spain, WLS 2019

Russia, WLS 2019

Latin America

Relative to other world regions, Latin America has experienced its fair share of issues with financial and political inclusion, as well as access to justice. Many of these issues stem from problems at the governmental level, creating a deep sense of distrust in many Latin American nations. According to one study, around 80% of Latin Americans believe their government is corrupt. These issues may relate to the upsurge in blockchain adoption and crypto economies. These technologies could provide opportunities for governments to reinvent their systems in a way that fosters trust in the financial and legal systems. Cryptocurrencies in particular have experienced tremendous growth across countries like Venezuela, Brazil, and Argentina, with Buenos Aires ranked as one of the top ten cities for bitcoin presence. In fact, Argentina is one of the only countries where crypto currencies are used for real world transactions.

“It is important to consider the construction of a citizenship that is an agent of social change, which implies forming open and dynamic management structures, as well as consolidating civic education processes (education for citizenship) that cover diverse social sectors, ages, etc., to generate co-creation systems of public value.” Panelist, Argentina, WLS 2019

The following excerpt on digital identity in Latin America has been adapted and expanded from its first publication in the WLS Special Edition E-zine published by Legal Business World.

Most Latin American nations now use some form of eID system with rapidly growing digital infrastructures for governing and managing these solutions. The most widely used e-credential system used across Latin America is the 2D barcode card, a card encrypted via a 2D barcode. To illustrate, note that, according to some, Latin America is becoming a world leader in the biometric market with increased government investment in security, facial recognition technologies deployment, and cybercrime prevention applications.

Belo Horizonte, Brazil WLS 2019

Mexico, WLS 2019

While the concept of Self Sovereign Identity (SSI) is taking hold in Latin American countries, it remains a mere philosophical concept in most developed nations. For instance, Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico support adoption of decentralized digital identity systems, predominantly based in blockchain infrastructure. Those same countries, along with Venezuela and Chile, also have widely accepted the use of cryptocurrencies in retail outlets and market places. For example, the Interamerican Development Bank (IDB) has launched LACCHain, a global alliance led by the Innovation Lab of the IDB to develop the blockchain ecosystem in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). An association of public and private actors at a national level across countries in Latam, LACChain has set as one of its main priorities developing a ‘techno-legal framework for self sovereign identity using blockchain’.

In addition, the concepts of digital citizens and digital governance are taking hold in parts of Latin America. In Brazil for example, Decree no 8.638, January 15, 2016 provides a framework for Digital Governance, and Decree no 8.936, December 19, 2016 provides the Digital Citizenship Platform for digital public services. However, the platform has received some pushback from the public.

The following issues were highlighted at the Brazilian locations of the 2019 WLS Summit:

- Lack of dissemination and guidance for broad knowledge and use by the population;

- Lack of a unique identity among all federated entities;

- No Digital Identity for access to all public services;

- Lack of homogeneity of single document use;

- Long wait times for access and complex information; and

- Large numbers of the population are digitally excluded.

Many Latin American nations are experiencing progress with technology adoption, with strong indication that with the continued development of DLTs and further consideration of new era identity frameworks, Latin America could leapfrog other world regions that do not yet have the technical infrastructure or skill base to further innovate with these technologies.

Although Latin America has made significant technological progress with both the adoption of DLTs and decentralized frameworks, including decentralized identity systems leading in the use of biometric data, this progress has not been matched within the government and legal systems. Technological progress has been spearheaded mostly by startup and innovation hubs operating independent of government funding. Similarly, citizens have adopted this technology without necessarily there being well structured regulatory environments in place. Much of that adoption sits outside of government regulation where regulatory frameworks simply do not yet exist or are poorly developed. Several Latin American countries, including Ecuador and Bolivia, have banned the use of digital currencies altogether, which could make blockchain adoption for other use cases – such as decentralized identity systems – more difficult.

Buenos Aires, Argentina WLS 2019

However, the regulatory environment for operating electronic identity systems is maturing quickly across Latin America given the widespread adoption of digital identity frameworks. While this is to be expected given the relatively early technical adoption of these systems, this rapid and early adoption has caused a problem where systems are incongruent between jurisdictions. For example, while Brazil has a technically mature digital identity infrastructure, including the use of biometric authentication across many of its states, no national level unified system that would enable voting or federal government services access exists. Brazil is currently running a National Civil Identification Program to acquire citizens biometric data in anticipation of developing a national ID system.

“There is a need to use the founding principles of the Brazilian Internet Civil Mark (the Brazilian Civil Rights Framework for the Internet).” Panelist, Curitiba Brazil, WLS 2019

Other challenges also exist, as highlighted in Mexico at the 2019 WLS summit where a legal vacuum was cited as one of the biggest challenges the country faces , especially since the country has regulations that talk about identity, data protection with no regulation on the issue of phishing in digital media and other basic concerns.

For systems like decentralized identities to gain large scale regional traction, consistency amongst jurisdictional stakeholders and at least a low level regulatory environment that facilitates the trusted operation of such systems are needed. The Brazilian efforts toward digital citizenship frameworks are certainly a promising sign, as are countries like Argentina that include concepts like the right to privacy, honor, and freedom of association in their national Human Rights Treaties with constitutional hierarchy. While much of Latin America is far ahead with adoption of DLTs and digital identity frameworks, truly decentralized systems at the government and international levels, will likely need to wait for cooperative legislative structures to be in place.

North America

Both Canada and the United States are surprisingly behind when it comes to the adoption of DLTs and digital identity frameworks. Though two of the leading blockchain networks, Bitcoin and Ethereum, have North American roots (though the exact origin of bitcoin is notoriously unknown). While these chains are largely responsible for the incredible growth of crypto economies worldwide in the last few years, both Canada and the United States have remained slow to adopt. This is true too of applications of blockchain and DLTs beyond cryptocurrencies, such as building decentralized identity frameworks.

One of the largest challenges facing AI are considerations surrounding data and identity, for example, “who owns the AI [generated] models of me?” Panelist Nashville, USA, WLS 2019

New York, WLS 2019

The following sections on digital identity and DLTs in North America have been adapted from its first publication in the WLS Special Edition E-zine published by Legal Business World

However, there are indications that Canada could be steps closer to a national eID program as early as this year (2020), and indications that the United States could too soon adopt. In the United States the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) are making dedicated efforts to speed up considerations of digital identities. The Obama administration put in place in 2011 a National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace, which the NIST in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Commerce has been actively working toward the implementation of. In Canada citizens are demanding that the Canadian government invest more in the development of these frameworks, with a 2017 survey indicating that 70% of Canadians want to see the government work with the private sector to implement digital IDs. Furthermore, the Digital Identification and Authentication Council of Canada (DIACC), a nonprofit coalition of industry leaders and organizations, is making progress with the development of a “DIACC Trust Framework Expert Committee (TFEC)”; this committee will be dedicated to the development and adoption of a trusted digital identity framework.

One of the largest challenges facing AI are considerations surrounding data and identity, for example, “who owns the AI [generated] models of me?” Panelist, Nashville, USA, WLS 2019

In addition, Canada is progressing the dialogues around the interoperability of digital identity frameworks through the development of the Pan-Canadian Trust Framework (PCTF). Very much to its credit, the intention of this framework is not to develop a new system, but to adopt existing protocols, policies and infrastructure and to support the interoperability between jurisdictions. As stated on the github site:

“The PCTF facilitates a common approach between the public sector and the private sector. Use of the PCTF ensures alignment, interoperability, and confidence of digital identity solutions that are intended to work across organizational, sectoral, and jurisdictional boundaries. In addition, the PCTF supplements existing legislation, regulations, and policies.”

While the progress in DLT considerations and adoption are not nearly level with that of digital identities, there have been some notable steps in the right direction. For example, there is general acceptance of the merits of these technologies as well as their application in government systems, with some signs of adoption. For example, the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) piloted a use case for blockchain technologies to improve data quality and to facilitate the more transparent shipment of goods. This is similar to the IBM Maersk use case for shipping and global trade, announced in 2018 originating in the United States. It is a global collaboration between more than 90 organizations including over 20 port and terminal operators worldwide. It is possible with the learnings from these programs, plus the considerations of digital identity frameworks, that Canada and the United States could be well positioned for the wider adoption of decentralized systems, including for identity management.

As with most other jurisdictions, one of the largest barriers to adoption of these technologies in North America is the lack of an appropriate regulatory landscape. In Canada the most work in the development of these legal frameworks has been done with regard to digital currencies, particularly crypto currencies, however these currencies are still not recognized as legal tender. Like with Canada and the global blockchain industry, the United States has put much of their regulatory attention at the administrative and agency level (e.g. the Securities and Exchange Commission “SEC” and the Federal Trade Commission “FTC”), with a primary focus on crypto currencies and the entities controlling them.

On Robot Rights, “should machine systems that operate independently of humans have a unique and separate legal identity?” Toronto, Canada, WLS 2019

Toronto, Canada WLS 2019

In addition, given the unrelenting growth of crypto currency use and adoption in nefarious underground cyber worlds (a.k.a the “darknet”), the United States has felt the pressure of needing standards and modes of governance to respond to these bad actors (rightly so). The U.S. government has launched the Cryptocurrency Intelligence Program as a response, implicating new tax reporting and regulatory requirements. For example, taxpayers are now required to report any income obtained via virtual currency use. However, there has been little to no consideration of the regulation of infrastructural applications of DLTs, such as for digital identity management.

With regard to digital identity legislation and regulatory management, there too has been little real progress in Canada or the United States. This is perhaps not surprising given that adoption of the technologies themselves have been slow moving. However, there are signs that this dialogue could become prioritized within the coming years. For example, with Obama’s 2011 National Strategy in the United States, and the DIACC having published a recommendation for a digital identity framework as follows:

- A set of rules and tools designed to help businesses and governments to develop tools and services that enable information to be verified regarding a specific transaction or particular set of transactions.

- Comprised of industry standards and best practices that define the processes to be followed to verify information about a person or a legal entity.

- Will help solutions to seamlessly work – or interoperate -“ together by establishing a baseline of requirements of public and private sector services.

Furthermore, there has been significant progress in the development of blockchain legislation, and its related concepts of identity, at the state level. For example, Wyoming is positioned to become a global leader in the discussion of the concept of ‘self sovereign identity’ in its legislature. The proposal for inclusion of such a concept and its definitions comes as a response to the need for better definitions of a person’s identity in the digital world as represented in the legal domain. Current definitions of identity assume analogue methods of verification and protection, and are not fit for the modern age.

Given the slow rate of progress of both the technology adoption and development of regulatory frameworks for both DLT and digital identity technologies, it is unlikely Canada or the United States is to adopt a more decentralized outlook soon. Though, there are interesting signs that this could change quickly if these things become an investment priority. For example, the USA’s DIACC’s recommendations and Canada’s PCTF are promising. These recommendations state the demand for capabilities such as verifiability and interoperability of a future trusted identity framework. These statements allude to DLT enabled frameworks, which by their very essence provide for trusted, verifiable, and interoperable systems.

AI & Autonomous Systems

Africa // Asia Pacific // Europe // Latin America // North America

Introduction

Autonomous systems are those that operate tasks and goals and interact with a given environment with minimal to zero human support. When we consider the functioning of future global systems, their autonomy from centralized bodies (whether that be governments, corporations, or other institutions) is a critical aspect of their sustainability. That is, these systems will function by a mechanism of machine enabled rules and decisions that can self-execute and can be independent of one centralized authority and perhaps human involvement at all. While self-executing algorithms are not AI dependent, truly autonomous systems do need to learn from, predict, and adapt to the inputs they’re receiving and use the latest developments in machine learning (a subfield of AI) to accomplish this.

It is this intersection of AI and self-executing systems that is explored in this section reviewing their regulatory environment across jurisdictions. While more traditional AI considerations, e.g. the usage and protection of data enter this discussion, the main focus is on surfacing those regulatory environments that are considering the granularities and risks of AI enabled autonomous systems; for example, mechanisms for determining legal culpability of the system or at which point does the system become recognized as a legally independent entity, if at all.

While regulation dealing with autonomous vehicles or weapons may not directly address these granularities, they are still included in these considerations as there are aspects that can be applied to an approach that considers the more generalized regulatory environment for AI enabled autonomous systems.

Africa

African countries have not traditionally been an epicentre for AI research and development, however that is changing rapidly with the growth of the technology and innovation ecosystem and the introduction of Big Tech players like IBM and Google. According to The World Bank, technology and innovation clusters are increasing at a rate of 15% per year which is a fairly recent status for the continent. While it’s unclear exactly how many of these resources are dedicated to the research and development of AI, groups such as the Machine Intelligence Institute of Africa have illustrated significant progress in these domains. There is indication of continued growth with factors such as recent proliferation of research and development centres like Google’s AI hub in Ghana, and nation super hubs like Nigeria and South Africa with more than 8 technology hubs; though, as indicated above, it is unclear how much of the resources of these super hubs is focused on AI.

“Panelists at the Nigeria WLS2019 summit highlighted that one of the world’s top robotics engineers is from Nigeria, his name is Silas Adekunle and works with Apple Inc.”

While a lot of this growth is due to private sector investment in these hubs, a strong indication of continued growth could be the continued investment in organic, multi-stakeholder lead hubs; given that these types of ecosystems operate more proficiently than independently lead hubs run by government, the private sector, or academia. For example, two major AI hubs are spearheaded by big tech firms IBM and Google, though they work in partnership with local institutions and governments to solve some of the most pressing issues faced by local populations. As a case in point, in 2016 the Johannesburg IBM team worked with the government to improve the cancer reporting system in order to better inform health care policies.

Jos, Nigeria WLS 2019

Jos, Nigeria WLS 2019

Although there are signs of ongoing growth, there is a need to improve investment opportunities, skill development and digital infrastructure. One of the largest barriers African nations face to the adoption of AI is a lack of a strong digital infrastructure to support the many startups progressing these technologies. In particular, the internet infrastructure is poor and AI solutions demand powerful connectivity for data processing and scaled adoption. As a testament to these issues, only 12 African nations are included in the top 100 countries listed in the 2019 Government Artificial Intelligence Readiness Index compiled by Oxford Insights; a sign that there is a need for investment in digital resources if African nations are to continue to grow in these domains.

“… laws [dealing with autonomous machines] are too bureaucratic and may be a hindrance to technologists to even comply with. The overall effect will be to stifle innovation of emerging technologies…moreover, Kenyan laws don’t anticipate automated machines.” – Panelist, Kenya, WLS 2019

Regarding autonomous systems, it seems that adoption, at least at the experimental level, is taking place in some African nations. At the 2019 AfricaCom, the largest telecoms and technology event in Africa, it was announced that the Eastern and Southern African Trade and Development Bank (TDB) has successfully closed a US$22 million deal, transacted via smart contract technologies. While it’s unclear whether this particular use case made use of AI enabled components, it is a large scale use case for the adoption of ‘self-executing’ systems, where AI is enabled this could be a stepping stone toward the adoption of truly autonomous systems. Given that there are very few large-scale, real-world use cases (similar to this TDB scenario) across the globe, this could be a significant indication that at least some African nations could become global leaders in the adoption of autonomous systems in core capacities such as their economic infrastructure.

While the research and development of AI is certainly healthy, and there are signs of autonomous system technologies being adopted, the regulatory environment is still severely underdeveloped. Of the 12 African nations that are part of the top 100 AI Government Readiness Index, there are effectively no legislative frameworks for the management of AI and related autonomous systems. Of the countries that are putting substantial resources into AI considerations, most (if not all) are task forces and planned or recommended national strategies focused on the research and development of the technologies, as opposed to building a regulatory environment. Often these groups and strategies are not AI specific and rather are directionally geared more toward preparing these nations for the fourth industrial revolution with regard to several technologies, often neglecting some of the nuanced requirements of an effective AI strategy.

“The only piece of legislation which really touches on AI at the moment is the South African Civil Aviation Authority’s Remote Piloted Aircraft System (RPAS) regulation. These regulations cover the use of semi-autonomous drones, but are really designed around pilot training and don’t mention governance of AI systems.” – Panelist, WLS 2019

Uganda, WLS 2019

Algeria, WLS 2019

For example, South Africa and Uganda have a commission dedicated to the fourth industrial revolution. Both countries focus on broad based approaches to ensure the preparedness of their systems for the demands of new technologies and building global competition, such as in the domains of blockchain, 5G and AI. Of these approaches, it is unclear if the impact of autonomous systems specifically, meaning self-executing machine enabled decision making, is considered at all. However, in Kenya a DLT based logistics company is making use of smart contracts to increase the authenticity and transparency of import and export documentation; perhaps indication that a regulatory environment will emerge at least for these use cases.

In addition, in Kenya the Civil Aviation Regulations (RPAS, 2018) does address the use of drones, and insofar as drones are considered ‘autonomous machines’ then it could be suggested that there is some consideration of these systems in the current regulatory environment; although, ‘autonomy’ is not specifically addressed and, as indicated below, is a nascent concept in Kenya. Further, this particular regulation has since been repealed by parliament on the grounds that there was insufficient public consultation, and safety concerns for privacy and persons. WLS2019 panelists stated further issues with the legislative environment “… laws [dealing with autonomous machines] are too bureaucratic and may be a hindrance to technologists to even comply with. The overall effect will be to stifle innovation of emerging technologies…moreover, Kenyan laws don’t anticipate automated machines.”

Asia Pacific

According to an IDC report, as of 2018 37% of organizations across the APAC region had plans to adopt AI capabilities over the next 5 years, with the prevailing application of interest being improved business insights. Though, as of the 2018 IDC report AI adoption rates were just 14% across Southeast Asia. However, some nations are prioritizing AI adoption far above others in the region, with 80% of China and South Korean companies considering AI adoption to be mandatory for business success. The report also stated that Singapore was surprisingly at just 9.9% adoption rates, however that same year the “AI Singapore” initiative was launched to “anchor deep national capabilities in AI, thereby creating social and economic impacts, grow local talent, build and AI ecosystem and put Singapore on the world map.”

Though the APAC region has traditionally been a leader in early technology research and adoption, it is amongst the lowest rated regions on the 2019 Global AI Readiness Index. However, it is worth noting that China has a rating of 7.37 on a scale to 10, relative to expectations it has a rating of 20th in the top 100. Singapore does take the 1st position in the top 100, with a strong economy, attention to governance, and investment in innovation – perhaps an indication of the importance of having strong regulatory, technological and research foundations, coupled with private-public partnerships. It is important to point out that the index is not complete with data for all categories, perhaps adding to an imbalance in the overall rating for the APAC region. For example, much of China is already adopting AI in government systems, with the implementation of a “robot judiciary” that has already processed millions of legal cases across China, amongst other applications.

Singapore, WLS 2019

Singapore, WLS 2019

“Dr Alan Davidson, TC Beirne School of Law, UQ urged legal practitioners to start considering the array of issues – legal or otherwise – that come with integrated autonomous machines. Using the Moral Machine Test (MIT) and German ethical rules, Davidson presented a series of thought-provoking scenarios to the audience to open up the conversation around the ethical and moral dilemmas surrounding autonomous [systems].” – Panelist, Brisbane Australia, WLS 2019

While actual legislative frameworks are yet to be developed across the APAC region, there are signs that lawmakers are headed in that direction. According to the International Institute of Communications, there are five core areas for which law and policy-makers are considering across the region: infrastructure, access to data, skills and human capital, trust and partnerships, and ecosystems and entrepreneurship. Predominantly, the strategies and frameworks that are emerging across the region with these topics at their core are focused on “[harnessing] the power of AI” as opposed to development of the regulatory landscape to manage AI enabled and autonomous systems.

“There are broad gaps regarding liability and insurance. It is unclear who is at fault, who would be held liable for damages, and whether insurance exists for mass adoption of autonomous/automated machinery.” – Panelist, Adelaide Australia, WLS 2019

Sydney, Australia WLS 2019

However, there are nations within APAC that are making headway on some of the more pressing concerns around AI ethics and regulatory oversight. For example, the Australian government has published insights and guidelines for the development of an AI ethics framework. A similar model has been released in Singapore by the Personal Data Protection Commission titled the Model AI Governance Framework. In collaboration with the World Economic Forum, and based on the model framework, Singapore released a guide titled the Implementation and Self-Assessment Guide for Organizations (ISAGO). Borrowing from the model framework the ISAGO considers four main domains:

- Internal governance structures and measures

- Operations management

- Determining the level of human involvement in AI-augmented decision making

- Stakeholder interaction and communication

These are so far very light enforcement measures though, that effectively amount to voluntary assessment and compliance. The Australian framework is so explicit as to state that the components of the framework so far include, “a set of voluntary AI Ethics Principles to encourage organisations using AI systems to strive for the best outcomes for Australians”. There is no real body of authority to monitor or ensure some measure of adherence to these guidelines.

“… current regulations implicitly assume that there is human control.” Panelist, Sydney Australia, WLS 2019

It is important to note that while these frameworks are currently quite light, there are nonetheless many existing frameworks, such as personal data protection laws, that may apply in the region insofar as personal data is used in the training of AI models. In this regard, it is not necessarily the case that the regulatory environment for AI is completely nascent, or that there are absolutely no actual laws to govern the use of AI technologies. Instead, it is likely that other domains of law or even sector specific applications of law may address needed aspects of AI regulation. For example, the regulation of data use in machine processing may be covered under data protection regulations, though it does specifically address an aspect of AI governance.

Though some nations, such as China and Japan have taken more granular steps in addressing the root of ethical concerns for AI. The Beijing AI Principles were released in 2019, and offer guidelines for engineers and scientists who are actually developing these technologies. In Japan, there have been a series of finer tuned efforts, such as the development of “Contract Guidance on Utilisation of AI and Data” which could amount to a set of guidelines for autonomous or ‘self-executing’ systems like smart contracts, given that it addresses the drafting of contracts involving AI and data based systems. Furthermore, with regard to autonomous systems specifically, there have been sector specific developments in regulatory systems; for example, the Ministry of Transportation in Singapore is actively working with cities and automobile manufacturers to construct an appropriate regulatory landscape for the adoption of these vehicles.

Europe

Relative to world leaders much of Europe is lagging behind in its adoption of AI technologies. According to McKinsey’s AI readiness index there is quite a bit of diversity in the landscape across European countries. For example, with countries like Ireland and Sweden leading in automation, but are doing less well in the area of AI startups. Whereas others like France and Denmark though leading in automation, are overall doing comparatively poor in other categories.

Opinion Piece by Brendan Guildea, Ireland WLS2019 “Emerging Trends in 21st Century Technology Regulation”

“Major adjustments were done in the beginning of the 80’s. We see a legal condition [where] collection of data is possible only by means of routine measures. However, routine measures introducing AI will broaden the principle, which is a challenge. SE law has made adjustments, but with AI this will be even more comprehensive.” – Panelist, Sweden, WLS 2019

However, the Government AI Readiness Index suggests a different European landscape, with several of the top 20 countries on the 2019 index being Western European nations. This is due in large part to the already efficient and digitally inclined governments of these nations, and the investment from the private sector in innovation. For example, there is a unit of the EU focused on Robotics and Artificial Intelligence, which explicitly addresses the development of competitive industry in the field of autonomous systems. As is to be expected, many of the nations listed in the index also have national AI strategies. The Eastern European index has an overall average rating that is several points above the global average, with countries like Estonia and Latvia leading for this region. Here, skills in AI are amongst the reasons for some nations’ readiness score. Estonia in particular has already adopted AI capabilities in some of its government infrastructure. These countries are also members of the Declaration on AI in the Nordic-Baltic Region, and effort to ensure cooperation for Industry 4.0 and particularly collaboration on AI efforts.

“The Robo Law initiative is an absolute reference at the European level for considerations in dealing with Robotics, Laws and Ethics.” – Panelist, Barcelona Spain, WLS 2019

Dublin, Ireland WLS 2019

In 2018 the European Commission announced a strategy to encourage the investment in research and development across its member nations, with a goal of US$22.5 billion invested by the end of 2020 through coordinated efforts. Russia too is prioritizing AI investment, with an estimated US$12.5 million per year spent on research. Though, that is perhaps not surprising given that Vladimir Putin reportedly stated that “whoever becomes the leader in [AI] will become the ruler of the world.”

The European Commission has taken a somewhat more proactive approach to the inclusion of ethical concerns about AI and autonomous systems in its considerations, relative to other global regions. In 2020 a paper was published by the EU titled “On Artificial Intelligence, A European Approach to Excellence and Trust”. The emphasis on trust suggests the interest in pursuing frameworks and strategies that take into consideration nations citizens concerns with the technologies. This sentiment is summed up in this statement from the commission and how it is, “… committed to enabling scientific breakthrough, to preserving the EU’s technological leadership and to ensuring that new technologies are at the service of all Europeans – improving their lives while respecting their rights.”

This paper is in response to a promise by the new president of the European Commission, Ursula Von Der Leyen, that legislation addressing frameworks to manage AI technologies would be put in place. This promise comes with the intent to take an AI-risk mitigation approach, where other world regions are less focused on the risks or ethical considerations. An example of how this might be enacted is to determine high-risk AI systems, and to enforce certification before introduction to the market.

Furthermore, there were a series of proposals put forth by the European Parliament, on regulations for an ethical code for AI, and regulations on civil liability. And, individual countries in Europe have also been active in developing global initiatives. For example, France (together with Canada) formed the Global Partnership on AI with fellow G7 member countries and a few others (including Singapore).

Moscow, Russia WLS 2019

Paris, France WLS 2019

Beyond these efforts by the EU, the AI regulatory landscape across Europe is still fairly young. With for example countries like Switzerland having no national strategy at all and instead private organizations making recommendations, and others like Estonia only just introducing widespread government lead campaigns to further develop and research the application of AI technologies. Though, as noted above, whether strategies are in place or not some countries, like Estonia are already making use of AI technologies in their government systems. This is surprising given these countries traditional leadership in the adoption and regulation of emerging technologies.

“The major controversies on the use and legislation of autonomous machines relates to ethical issues arising from [the machines] coding and programming as well as concerning who must be held liable in case of accidents (e.g. the Uber case).” – Panelist Madrid, Spain

However, when it comes to autonomous systems some european countries are leading the way globally. For example, Belarus legislation on blockchain technology introduces legal definitions of smart-contract technologie, “ …program code securing the autonomous perfection, or fulfillment, of dealings with tokens, as well as of any other type of legal acts.” This is apparently the first definition of autonomous systems like smart-contracts to be adopted at a national level.

Latin America

The following sections on AI and Autonomous systems in Latin America have been adapted in part from first publication in the WLS Special Edition E-zine published by Legal Business World

According to the Global Talent Competitiveness Index (GTCI), produced by Google and other partners, Latin America is well positioned to become a leader in global AI talent. This has to do in part with many of these nations scoring high on AI preparedness indexes, with 15 of the 100 top nations listed in the GTCI report being Latin American countries. The nations leading the way are Mexico and Brazil, along with Uruguay and Chile. Much of the driver of this AI adoption is due to indications that these technologies could greatly improve Latin American economies. For example, some models estimate that the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of the Brazillian GDP would increase over 7% per year up to 2030 when the maximum benefits of AI are considered. In addition, with Latin nations like Brazil leading world wide in agricultural products, there are industry specific incentives for further development in autonomous machines and their applications.

Part of these developments are due to large scale government investment into the research and development of AI, with Mexico leading the way in 2018 as the first Latin American country to construct a national AI Strategy. This strategy is focused on the research and development of AI technologies, with much of this investment going to university research and postgraduate programs focused on AI. While this progress is a positive sign for Mexico’s participation in the global AI economy, there are concerns. During the 2019 WLS Summit panelists discussed the concerns of the rapid adoption of AI and autonomous systems and its displacement of jobs. There is concern that Mexico’s academic and labour infrastructure won’t be able to support the demands on the reskilling of workers and the readiness for taking on the new jobs that are emerging.

Belo Horizonte, Brazil WLS 2019

Argentina, WLS 2019

Though some nations are making moves to develop national strategies, it is worth noting that this move is not widespread across Latin America. According to Oxford Insights as of 2019 only two countries (Mexico as stated above, and Uruguay) are making moves toward the development of comprehensive AI policies or strategies. It is worth noting that the top 20 countries on the 2019 Global AI Readiness Index do not contain any Latin American countries.

Though since the publication of the 2019 index, there is indication that the landscape could be rapidly changing. For example, Argentina’s Secretary of Government of Science and Technology is in the process of developing a “National Plan of Artificial Intelligence”. In addition, in 2019 a bill was issued meant to address the regulation of AI in Brazil, and an ordinance was issued by the National Council of Justice (CNJ) to encourage the adoption of AI capabilities in Brazilian courts to support building efficiencies for effective case management.

Panelists at the 2019 World Legal Summit in Belo Horizonte Brazil indicated several considerations that legislation would need to review to begin addressing some of the challenges faced in regulating AI:

- the ethics of machine production (“how to produce”);

- defining the degree of autonomy of Artificial Intelligence;

- the regulation of machine-human symbiosis;

- the definition of criminal / civil liability (and degrees of guilt) with objective or jointly agreed requirements for imputing liability and sanctions.

Curitiba, Brazil WLS 2019

Mexico, WLS 2019

However, like with most jurisdictions worldwide, for the most part the national strategies that are in place are largely focused on building competitiveness in the research and development of these technologies in the global economy, and there is little consideration of the regulatory landscape. As a statement to this, Omar Costilla-Reyes, an MIT postdoctoral fellow and leader of AI ethics in Latin America, has said, “Latin America needs to be an ethics-first AI continent to guarantee that the technology will be developed and deployed for social benefit … such as [prevention of] the use of AI deepfakes to spread misinformation”.

“There is currently no consideration of autonomous machines in Brazillian legislation, and public consideration could be said to meet with ignorance and disinterest.” Panelist, Manaus Brazil, WLS 2019

North America

The following sections on AI and Autonomous systems in North America have been adapted from its first publication in the WLS Special Edition E-zine published by Legal Business World

Both Canada and the United States are often reported as leaders in artificial intelligence, in particular when it comes to research and development. In 2016 Canada announced a $1.3 billion fund for the research and advancement of artificial intelligence technologies. Canada also has two major cities leading the way globally, with Montreal having the largest pool of AI researchers worldwide and Toronto having the largest number of AI startups worldwide. In addition, the United States is widely considered to be a leader in the development of Artificial Intelligence technologies, based on a recent WIPO study that indicates that USA based companies and Chinese based companies make the large majority of AI patents issued. In particular, IBM and Microsoft (U.S. companies) currently hold first and second place for the most amount of AI patent applications. In addition, the U.S. leads in scientific papers citations for AI research according to the National Scientific Board of the USA. Furthermore U.S. courts are using an AI enabled tool called COMPAS to predict a defendant’s chances of recidivism; though it has been met with some controversy and backlash, given that at its time of use in 2017 there were no regulatory protocols to govern the use of the tool.

With regard to the adoption of autonomous systems, the United States is leading the testing and adoption of driverless vehicles being listed near the top of the list of KPMG’s 2019 readiness index. Furthermore, the use of smart contracts as a viable technology is being considered in detail by organizations like the Canadian Bar Association. In the United States several states have enacted a series of ‘blockchain enabling laws’ that are creating the environment for the adoption of smart contract systems, for example with Delaware allowing digital assets to be controlled by smart contracts.

Toronto, Canada WLS 2019

New York City, WLS 2019

Similar to other jurisdictions worldwide Canada and the United States are just recently seriously considering the implications of poorly governed AI and autonomous technologies. In 2017 Canada became the first country to launch a federally funded national strategy for AI managed by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. In addition, Canada has issued a directive intended to support the management of ‘automated decision making’. According to subsection 4.2 the intended results of the directive are as follows:

- Decisions made by federal government departments are data-driven, responsible, and complies with procedural fairness and due process requirements.

- Impacts of algorithms on administrative decisions are assessed and negative outcomes are reduced, when encountered.

- Data and information on the use of Automated Decision Systems in federal institutions are made.

Toronto, Canada WLS 2019

For the most part the United States regulatory environment for AI is at the state level. Several states have made moves to legislate and provide regulatory action toward the governance of the private sector. Though at the federal level in early 2020 there was a federal memorandum issued by the Office of Management and Budget, titled “Guidance for Regulation of AI Applications”. This memorandum considers the promotion of public trust in AI, the assessment of risks of AI, and fairness and descrimination in AI, amongst other items. Furthermore, the National Defense Authorization Act for 2019 does seem to take considerations of AI to a deeper level than its Canadian counterpart the Directive on Automated Decision-Making.

For example, subsection (g) of the Department of Defense’s activities include the following definitions of AI:

- Any artificial system that performs tasks under varying and unpredictable circumstance without significant human oversight, or that can learn from experience and improve performance when exposed to data sets.

- An artificial system developed in computer software, physical hardware, or other context that solves tasks requiring human-like perception, cognition, planning, learning, communication, or physical action.

- An artificial system designed to think or act like a human, Including cognitive architectures and neural networks.

With regard to autonomous systems there have been similarly few legal developments. With regard to smart contracts in particular, that is “self-executing algorithms” (a component of some autonomous systems), the Canadian government has been relatively deliberate in its moves to postpone the allowance of them, until the technology is further developed and regulatory structures are matured. However, there is indication that the use of smart contracts are being considered in the Canadian context. For example, the Canadian Bar Association has stated that smart contracts could be legally enforceable if they meet the conditions for the enforceability of a traditional contract.

“One of the largest challenges facing AI are considerations surrounding data and identity, for example, ‘Who owns the AI [generated] models of me?'” Panelist, Nashville, USA, WLS 2019

Similarly the U.S. has not had a case in which to set a precedent and does not have any current laws equipped to deal with cases involving the use or misuse of smart contracts. However, there are some elements of the existing legal framework dealing with the writing and signing requirements of contracts that could transfer to the use of smart contracts. For example, in a sense smart contracts could be argued to be allowed under the current Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) that indicates that contracts do not necessarily need to be in writing. It could be inferred that this could mean that not every contract needs to be in natural language, and could for example be in machine readable language or “smart contract” form.

Personal Data Governance

Africa // Asia Pacific // Europe // Latin America // North America

Introduction

Of the World Legal Summit’s ‘Technology Pillars’, personal data governance is the most mature in terms of available information and regulatory frameworks to draw insights from. With the advent of the European GDPR, the protection and management of personal data has come into the mainstream. Here we are focused on the legal frameworks that are considering persons as independent from the state, or as ‘self sovereign’ beings that exist in and cooperate within a given state or society, but that are not dependent on the state for their identity and the management or utility of it.

Given that we focus on future systems effecting and integrating our global society made up of individuals, this section considers the maturing legal landscape for the protection and governance of personal data. Related topics dealing with the broader scope of cybersecurity or general data management are not within scope, however insofar as they are related to the protection, management, or sovereignty of personal data they are considered.

Africa

With the second-largest population of internet users on the planet, and widespread use and speed of mobile devices across the continent, African countries are poised to reap the benefits of an increasingly digitized market and data management solutions. Despite its potential for becoming major players in the world data economy, the region risks becoming mere suppliers of data, as opposed to harnessing its economic power. Countries also face challenges related to privacy and personal protection of data.